Below are examples of intertidal greens from the surf-swept shores of the northern Oregon coast. A fair number of the green seaweeds pose identification challenges (for me!), so I’m happy with genus-level identifications when I can get there. My organization loosely follows Kozloff (1993) and Lamb and Hanby (2005), showing species you might encounter in the field, from highest to lowest in the intertidal. My photos are from northern Oregon unless noted, and common names, if I use them, are my choice. Experts cover the seaweeds shown below, and many more, in the resources listed at the bottom of this page.

Let’s explore some green seaweeds!

Prasiola

To find Prasiola on the exposed coast, follow gulls to the places they like to hang out during the highest tides.

Droppings would be abundant at any such haunt.

Tiny blades carpet portions of spray zone rocks.

You can see short stalks on some of the blades, which here are mostly rounded wedge- or fan-shaped, and the Seaweeds of Alaska account mentions the blades can have a hoodlike curve at the tip—I feel like you can see it in many of these. (For scale, the coin in the left-hand panel is just under 18 mm across.)

In the right setting, frequently at freshwater seeps, Ulva intestinalis can creep to the highest reaches of the splash zone and above. You can also find it in high tidepools. (I feature a few other common Ulva examples farther down on this page.)

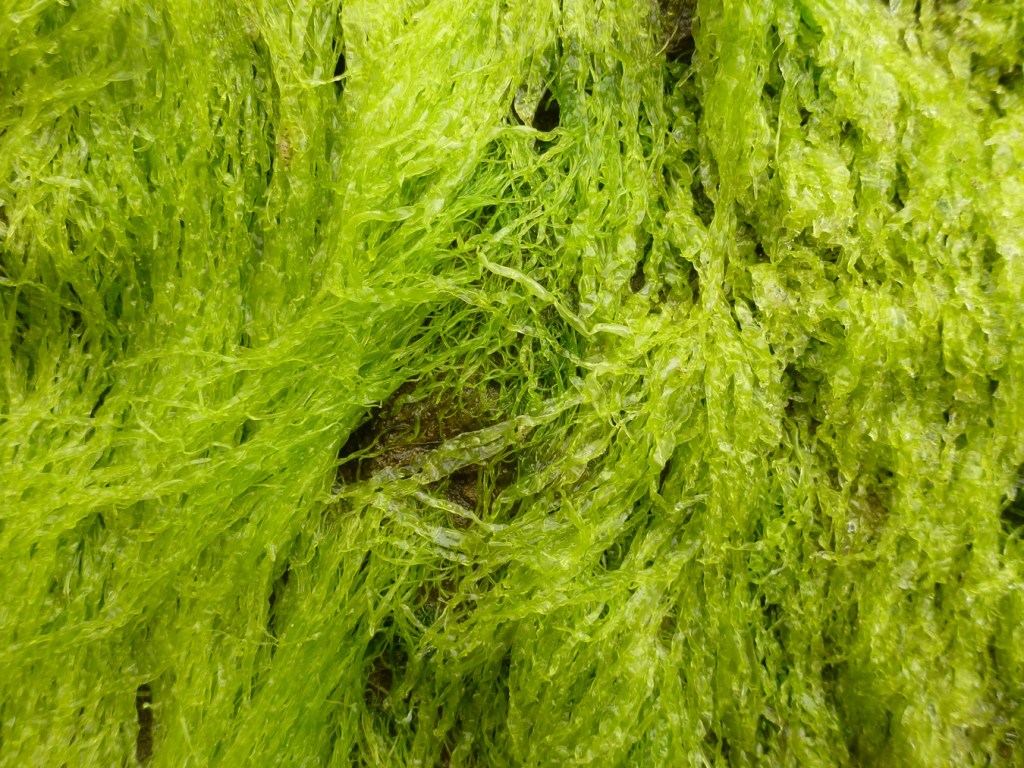

Though I’m not sure it is always the case, I feel like seep-dwelling U. intestinalis can be pretty dark green in winter and can stay that way into early spring. It reaches peak green chartreuse or yellow chartreuse later in spring and stays that way into summer. To illustrate this, the set below compares the same patch in March (left-hand panel) and July (right-hand panel).

In peak green or yellow chartreuse, a cascade of Ulva intestinalis is a sight of beauty.

***

Discovering lush tufts of Cladophora is a high (and mid, and sometimes even low) intertidal pleasure.

In the examples featured below, all from semi-protected mid-intertidal settings with lots of sand, the unbranched filaments have large cells visible to the unaided eye. With habitat and cell size in mind, one of the possibilities is Chaetomorpha. Further, Druehl and Clarkson say Chaetomorpha filaments resemble strings of emerald beads; I feel like that’s compelling and my examples are probably Chaetomorpha. (All of the images in this entry are from the outer central Oregon shore.)

You’ll bump into Ulva on the exposed coast sooner rather than later. Lush growth can occur under the right conditions, and Ulva diversity is enough to keep you interested (and you may have a few other feelings too) for the rest of your life.

This is one of those holey ones with broad, fan-shaped blades, maybe something like Ulva fenestrata. You sure wouldn’t be out of line calling it sea lettuce.

Ulva taeniata is pretty distinctive. It’s at home in and around sand-filled tidepools, and its common name, sea spiral, makes sense. (The three examples in the set below are from the central Oregon shore)

Long ruffled blades suggest Ulva linza, but that’s just a conversation starter. The examples below are from the edge of a semi-protected boulder field with plenty of sand.

While on the subject of green blades, below are two examples of epiphytes I’ve found washed up in the drift. In the top image, green blades hitchhiking on drifting Fucus. In the lower image green-bladed epiphytes on drifted eelgrass Zostera. Without too much else to go on, I think there is a decent chance these thin blades are in the notorious Ulva/Ulvaria/Kornmannia/Monostroma crowd. However, Druehl and Clarkston’s pragmatic reminder, “A definitive field identification of Monostroma is beyond the reach of mere mortals.” seems relevant.

Acrosiphonia coalita Green rope

The three examples in the set below are from the central Oregon shore

Codium fragile Sea staghorn

It’s uncommon, on the exposed beaches I frequent, to encounter drift Codium fragile, but it happens.

Codium setchellii Spongy cushion

References

Abbott, I. A., & Hollenberg, G. J. (1976). Marine algae of California. Stanford, Calif. Stanford University Press.

Druehl, L. D. and B. E. Clarkston. 2016. Pacific Seaweeds: A Guide To Common Seaweeds of the Pacific Coast. 2nd ed. Harbour Publishing Co.

Harbo, R. M. 2011. Whelks to Whales: Coastal Marine Life of the Pacific Northwest. 2nd ed. Harbour Publishing Co.

Kozloff, E. N. 1993. Seashore Life of the Northern Pacific Coast. 3rd ed. University of Washington Press.

Lamb, A. and B. P. Hanby. 2005. Marine Life of the Pacific Northwest. Harbour Publishing.

Mondragon, J., and J. Mondragon. 2010. Seaweeds of the Pacific Coast. Shoreline Press.

Sept. J. D. 2019. The New Beachcomber’s Guide to the Pacific Northwest. Harbour Publishing.

Web Resources

The Green Seaweeds page on the Netarts Bay Today website shows off a great lineup of local green seaweeds. Accessed January 28, 2025.

Seaweeds of Alaska is a standard reference for the Pacific northwest. It has a great Chlorophyta page. Accessed January 28, 2025.

The Seaweed Sorter app is fun and useful!

I updated this page on February 17, 2025